When it comes to managing stormwater, U.S. communities nationwide face many different regulatory frameworks and paths to achieving clean water. While some communities are building green infrastructure to reduce combined sewer overflows, others are installing stormwater controls as part of total maximum daily loads, while still others are implementing minimum control measures for municipal separate storm sewer system permits. From industrial to agricultural to ultra-urban settings, the arenas for stormwater management vary greatly. Stormwater is a variable force, so the solutions must be equally adaptive. With such tools as manufactured treatment devices, nonstructural controls, green and gray infrastructure, and agricultural conservation practices, stormwater professionals can be better equipped to handle new challenges.

The following nine case studies share how some are developing the tools to overcome stormwater challenges. These solutions will be presented at the 2015 Stormwater Congress, a spotlight event at WEFTEC 2015, which will be held Sept. 26 – 30 at McCormick Place in Chicago.

1. Stormwater Solutions for TMDLs

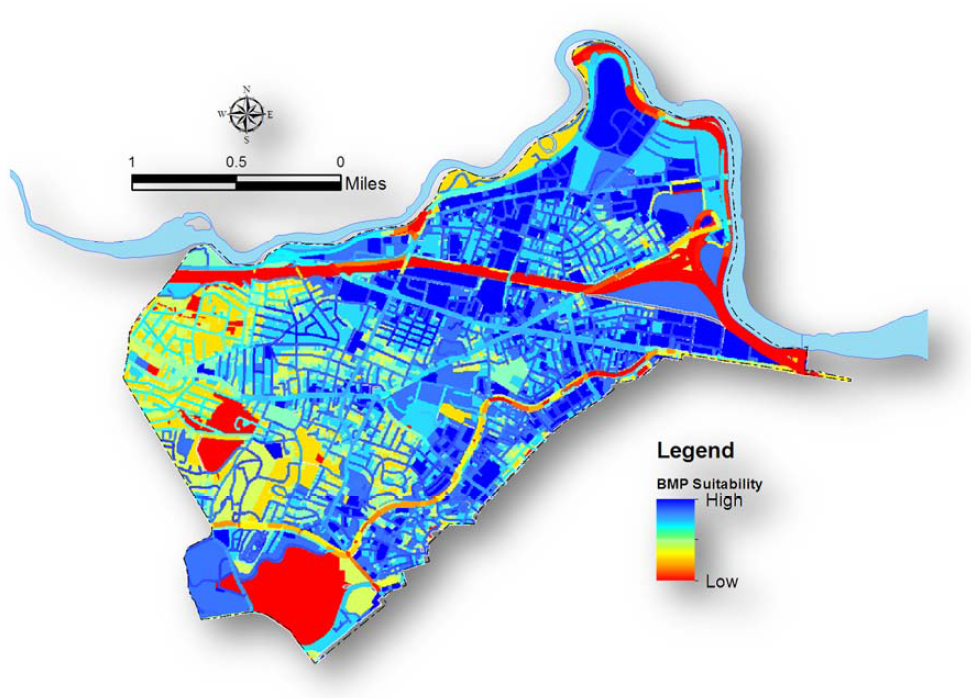

A best management practice suitability ranking in the Allston-Brighton neighborhood of Boston. Image credit: Boston Water and Sewer Commission

Many cities face stormwater requirements for combined and separate storm sewers and may have the added challenge of addressing impaired waters through total maximum daily loads (TMDL). While TMDLs specify the maximum amount of a pollutant that a waterbody can receive and still meet water quality standards, it does not address how sources should treat or reduce those pollutant loads.

To meet a TMDL for total phosphorus and pathogens in the Charles River Watershed, the Boston Water and Sewer Commission is developing a best management practice (BMP) recommendation plan. To prioritize potential BMP implementation, Dingfang Liu — formerly a senior technical consultant with CH2M Hill and now a principal engineer at Kleinfelder — and other CH2M consultants, developed a quantitative, geographic-information-system-based ranking process. The rankings account for both the physical suitability of sites — which includes such factors as site conditions or whether the location is a pollutant hot spot — as well as the likelihood of implementation, which accounts for social and economic conditions. Before this analysis, Liu and others also screened BMPs for their effectiveness at removing total phosphorus and pathogens.

The final implementation plan must be a multi-phased, adaptive approach. Communities first should pilot projects and expand their action plan from this early phase based on experiences gained from monitoring and evaluating pollutant load removal efficiencies.

2. Non-Structural Stormwater Solutions

The City of San Diego has developed a first-of-its-kind methodology for quantifying the effects of dozens of nonstructural stormwater strategies, including outreach and education programs.

Within its stormwater permit and as part of a TMDL, San Diego must identify BMPs and the effects of those BMPs on various pollutants as well as anticipated water quality changes. To quantify the effects of non-structural controls, the analysis included the level of control the city has over the strategy as well as constructs affected by outreach campaigns, such as guilt and social norms.

A percent removal range was developed for each of the pollutants removed by various BMPs. The removal range could be as low as 2% for a minor pollutant that is only partially affected by a certain BMP up to 72% for a major pollutant where the city has significant control over the management strategy.

This study provides a starting point for estimating the potential pollutant load reductions a city may achieve with non-structural strategies, said Stephanie Shamblin Gray, a water and wastewater engineer with HDR and the project lead. “This is a theoretical approach, so the follow-up challenge is quantifying actual reductions through monitoring.”

3. Agricultural Stormwater Solutions

Researchers monitor and evaluate agricultural runoff and the effectiveness of agricultural conservation practices. Images by Stone Environmental

Lake Champlain in Vermont — the sixth largest freshwater lake in the U.S. — is considered impaired by phosphorus, and EPA is expected to issue a TMDL for the lake this summer. The agency’s modeling efforts show that runoff from agricultural lands is responsible for almost 40% of the lake’s annual phosphorus load. While agricultural landowners have made significant investments in BMPs, these efforts have not yet yielded desired water quality results nor have site-specific benefits of the BMPs been quantified. However in 2012, the Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food & Markets, in partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resource Conservation Service, the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources, and the Lake Champlain Basin Program, initiated the Agricultural Practice Monitoring and Evaluation Program

Lake Champlain in Vermont — the sixth largest freshwater lake in the U.S. — is considered impaired by phosphorus, and EPA is expected to issue a TMDL for the lake this summer. The agency’s modeling efforts show that runoff from agricultural lands is responsible for almost 40% of the lake’s annual phosphorus load. While agricultural landowners have made significant investments in BMPs, these efforts have not yet yielded desired water quality results nor have site-specific benefits of the BMPs been quantified. However in 2012, the Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food & Markets, in partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resource Conservation Service, the Vermont Agency of Natural Resources, and the Lake Champlain Basin Program, initiated the Agricultural Practice Monitoring and Evaluation Program

BMP performance data and accurate pollutant reduction estimates will help to inform the TMDL process and have led to unexpected insights about managing agricultural runoff. “Our expectation was that most of the phosphorus leaving farm fields would be in particulate form and attached to soils,” said Julie Moore, water resources group leader with Stone Environmental Inc. and principal investigator for the study. “It was unexpected to see how much of the phosphorus being lost in runoff was in the dissolved fraction as compared to the particulate fraction.” Because particulate phosphorus has been the target of most conservation measures promoted to date, BMPs have relied on reducing soil loss to achieve phosphorus reductions.

Not all agricultural runoff is created equal. Learning that runoff from Vermont farm lands can have significant dissolved phosphorus concentrations changes the types of BMPs landowners should consider. Additionally, agriculture often is seen as the low-hanging fruit in areas with nutrient pollution problems. However, variables like day-to-day management decisions can overwhelm the annual benefits of other BMPs. For instance, a wrong manure application timing can generate a significant amount of phosphorus runoff almost regardless of the BMPs that have been implemented.

4. Stormwater Solutions in Dense Urban Areas

Above: Visualization of the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission’s (SFPUC) Yosemite Creek Daylighting Project. Below: SFPUC’s Chinatown Green Alley Project. Renderings by AECOM

The San Francisco Public Utilities Commission (SFPUC) is implementing green infrastructure as part of a 20-year, multi-billion dollar effort to upgrade the city’s aging sewer infrastructure, which is 90% combined. Initially, the city will construct and monitor eight Early Implementation Projects — ranging from creek daylighting to green street projects — one in each of San Francisco’s urban watersheds. This pilot will inform citywide implementation of green infrastructure as part of the Sewer System Improvement Program.

However, integrating stormwater management into the city’s already heavily utilized and many-times constrained streetscape right-of-ways requires careful planning, public outreach, and innovative design responses. When implementing such surface improvements as green infrastructure into a city as dense as San Francisco, it is critical to integrate with other planned projects to achieve multiple community priorities, said Kerry Rubin, an ecological engineer and green infrastructure specialist with AECOM and SFPUC’s program management consultant for sewer infrastructure. The concept of placemaking is a multi-faceted planning and design approach that capitalizes on community assets to create public spaces that promote people’s well-being. Integrating stormwater management and placemaking provides an important opportunity to create functional urban landscapes while providing greater community value through traffic calming and community greening and by providing wildlife habitat, gathering spaces, and other improvements. Crucial to placemaking in dense urban environments is public outreach. SFPUC informed and engaged stakeholders, but also used public outreach to gain an understanding of local issues and preferences to build better projects while meeting community needs.

Cities adding green infrastructure should identify priority areas for stormwater management and set minimum performance criteria. Next, the cities can seek opportunities to integrate stormwater management into larger planned projects. Integrating with other projects creates cost efficiencies as well as synergies in planning, construction, and public outreach. Learn more about this project at WEFTEC in Session 514, “Integrated Stormwater Planning Case Studies.”

5. Green and Grey Stormwater Solutions

Above: A conceptual rendering of green infrastructure systems in Adams park in Omaha, Neb. Image by: Vireo; design by CDM Smith. Below: A green infrastructure pilot area in Kansas City, Mo. Image by: CDM Smith; design by URS

In addition to being part of a holistic solution for addressing combined sewer overflows and flooding, gray infrastructure — such as pipe networks, curb and gutters, and inlet and outlet structures — also plays a role in collecting and conveying stormwater to green infrastructure systems.

In addition to being part of a holistic solution for addressing combined sewer overflows and flooding, gray infrastructure — such as pipe networks, curb and gutters, and inlet and outlet structures — also plays a role in collecting and conveying stormwater to green infrastructure systems.

While there may be a great open space to create green infrastructure, the system will not work unless stormwater can get to it, said Brenda Macke, water resources engineer with CDM Smith and an expert at designing conveyance systems and green infrastructure for separate and combined sewer systems.

Between overland flow and pipe systems, designers must consider the amount of water green infrastructure systems are receiving and understand what the system can handle. For instance, an upstream pipe system may be able to convey flows from a 10-year storm, but the green infrastructures systems may be designed to treat smaller, more frequent storm events. Determining the thresholds for each piece and considering how green infrastructure systems receive water from and overflow back to the gray pipe system enables communities to optimize both systems.

The implementation of green infrastructure does not mean traditional gray infrastructure design can be ignored. In fact, the effective integration of gray and green design elements is critical in developing sustainable designs that meet regulatory requirements, enhance neighborhoods, increase cost efficiencies, and reduce long-term operations and maintenance.

6. Industrial Stormwater Solutions

Installation of modular wetlands at the Port of Tacoma in Washington State. Images by Port of Tacoma and Kennedy/Jenks Consultants

The Port of Tacoma in Washington State is a leader in industrial stormwater treatment innovation. The port’s industrial general stormwater permit contains some of the most stringent requirements in the nation. The port recently installed three different types of proprietary stormwater treatment equipment to reduce zinc concentrations in runoff at three unique but linked industrial sites. Looking to increase the number of tools in its stormwater management toolbox, the port is exploring the effectiveness of various treatment devices the port environment. Two of the installations represent the first ever application of the technologies at an industrial facility.

The Port of Tacoma in Washington State is a leader in industrial stormwater treatment innovation. The port’s industrial general stormwater permit contains some of the most stringent requirements in the nation. The port recently installed three different types of proprietary stormwater treatment equipment to reduce zinc concentrations in runoff at three unique but linked industrial sites. Looking to increase the number of tools in its stormwater management toolbox, the port is exploring the effectiveness of various treatment devices the port environment. Two of the installations represent the first ever application of the technologies at an industrial facility.

Ross Dunning, stormwater practice leader with Kennedy/Jenks Consultants, helped the Port of Tacoma evaluate options for the three facilities — all of which are flat, completely paved, and subject to extremely heavy equipment traffic. The site’s conditions and stormwater runoff characteristics as well as the design and treatment capabilities of the individual approaches played key roles in their selection. An additional consideration was system flexibility. “One of the unique challenges ports face is that stormwater characteristics can change based on what commodities the port is handling.” Dunning said.

While product cost often is a deciding factor, designing proper system hydraulics affects costs more, said Dunning. Accordingly, he said he uses hydraulic modeling to select gravity-based solutions whenever possible. If electricity was needed to pump stormwater to the systems at these three sites, project costs would have doubled at two sites and tripled at the third, he said.

There is no one proprietary or open-source solution – many considerations go into picking the right treatment approach, but nothing works if it is not maintained. Learn more about this project at WEFTEC in Session 213, “Stormwater Treatment Device Research.”

7. Stormwater Solutions for Groundwater Recharge

The trend in stormwater permits is to encourage infiltration to reduce stormwater pollution. In light of water supply issues, groundwater augmentation also is becoming increasingly important. “We should be collecting the rare water we have and making good use of it,” said Martin Spongberg, a senior engineer with Amec Foster Wheeler.

However, some water quality experts have questioned whether infiltration-based practices could degrade groundwater quality. The Los Angeles Basin Water Augmentation Study, led by the Council for Watershed Health — a Los Angeles-based nonprofit — in partnership with eight local, state, and federal agencies, sought to answer that question with long-term, comprehensive subsurface monitoring at six southern California infiltration sites.

Over the long-term, researchers saw no negative effects on groundwater quality. In some cases, infiltration even decreased the concentration of groundwater pollutants due to dilution and filtration by soil media. “There is a really low potential for augmentation to negatively impact groundwater quality,” said Spongberg, who has been the consultant program manager since 2003. However, areas with recalcitrant pollutant loads, such as salts or nitrates, or areas with very shallow groundwater may not be suitable for infiltration, he said.

A time concentration chart for chloride at Los Angeles National Veterans Park. SW designates stormwater sampling points, LS designates lysimeters, and MW designates monitoring wells. Well MW-04, which shows an increasing trend over time, is a background well not influenced by infiltration.

Groundwater augmentation has a cascade of multiple benefits, from reducing runoff to benefiting groundwater quantity and, in many cases, groundwater quality as well. It also can reduce greenhouse gases by augmenting local water supplies and decreasing or eliminating the need to pump water long distances.

8. Solutions for Stormwater Volume Reduction

Transportation systems present unique stormwater management challenges in that they cross many variable conditions, basins, and infrastructure. A 2008 National Academies of Sciences report identified roads and parking lots as the most significant land use with respect to stormwater pollution, as they constitute as much as 70% of total impervious areas in ultra-urban settings and typically export more pollutants than other impervious land covers. According to the report, maintaining predevelopment conditions is essential to managing stormwater discharges. Capturing stormwater volume and preventing runoff not only reduces the amount of pollutants flowing into surface waters but also reduces the water’s energy in downstream channels.

Eric Strecker, a principal water resources engineer with Geosyntec Consultants and one of the highway report authors, said transportation agencies should ask the following four questions. First, can the water be infiltrated? For instance, are the soil conditions and groundwater depths appropriate? Second, should the water be infiltrated? For instance, will infiltration cause slope stability issues or introduce pollutants into the groundwater? Third, how should water be infiltrated? And, fourth, how much should be infiltrated?

“We have to think through the potential outcomes of any management strategy to be sure we aren’t solving stormwater problems while creating other problems,” Strecker said. “We need to consider the entire watershed, both surface and subsurface components. In the grand scheme, we are not erasing that water; it is either going to run off, infiltrate, or evapotranspire.”

9. Technology as a Stormwater Solution

Above: Installation of the outlet structure that will hold optimized real-time controls. Below: Two rows of 10-in diameter perforated corrugated pipe in place. Images by Capitol Region Watershed District

Curtiss Field Park in City of Falcon Heights, Minn., is a first-ring suburb of St. Paul. The park contains a small, landlocked stormwater pond that receives runoff from approximately 15 ha (38 ac). With a history of flooding, the pond presented a safety concern until the implementation of an innovative technology solution.

Curtiss Field Park in City of Falcon Heights, Minn., is a first-ring suburb of St. Paul. The park contains a small, landlocked stormwater pond that receives runoff from approximately 15 ha (38 ac). With a history of flooding, the pond presented a safety concern until the implementation of an innovative technology solution.

The Capitol Region Watershed District installed a large underground detention and infiltration facility under an adjacent sports field. The system includes 119 m (390 ft) of large-diameter perforated pipe that stores and infiltrates floodwater from the pond. An optimized, real-time controller draws the pond down half a meter (2 ft) in advance of a predicted storm. This automated inlet technology added 58% more capacity to the system. With the real-time controller, the system achieves the same level of flood protection at half the cost of a second storage pipe alternative, which was estimated to cost $140,000 dollars.

Through its connection to the internet, the controller monitors national weather service information, and begins to draw down the pond when a particular size rain event is predicted at a predetermined percent probability. The draw-down thresholds can be changed as the district collects more data. At any time, staff can remotely login to the system to monitor performance and modify programming.

Evaluate new technologies to save money and enhance system operation. Stormwater professionals can learn from the wider water world by looking at how water and wastewater utilities are using automation technology, said Mark Doneux, administrator of the Capitol Region Watershed District. The district now is considering using automated controls to enhance the performance of water quality practices. Learn more about this project at WEFTEC in Session 515, “Flooding.”

Timely, noteworthy case studies–many pertinent to what DWSD-R and GLWA are wrestling with, planning and implementing to effectively advance water quality improvements and reduce BUIs to Great Lakes and associated tributary inland lakes, streams and connected water bodies in southeast Michigan. Well worth following up in approaching technical sessions, if attending.

Adaptive wet weather management, repurposing of vacant land and underutilized sewer, road, rail and other utilities infrastructure, adoption of vigorous stormwater ordinances, and disincentivizing conventional stormwater runoff drainage to combined collection system with green infrastructure and an array of on-site stormwater drainage alternatives, area-specific sewer separation in redevelopments, among other sustainable initiatives are finally emerging with leveraged public-private and grant-funded projects for benchmarking across many drainage districts within Detroit’s 140 sq mile highly urbanized, yet widely vacated and otherwise changed landscape.

DWSD’s pledged investment in $50M in GI through 2029, if not beyond, within certain drainage districts in Detroit will otherwise mitigate the frequency and volume of untreated CSOs to more impaired (sensitive) receiving waters and wildlife habitat, such as, that along the main branch of the Rouge River, tributary streams and wetlands.

Gary A. Stoll, Jr., EIT

DWSD, Wastewater Operations Group

Engineer, CSO Control, Green Infrastructure