Still in its early stages, the stormwater sector continues to evolve in a changing scientific and regulatory landscape. Stormwater champions across the U.S. and world are shaping this emergent field and have made significant contributions by trying innovative solutions that go above and beyond regulatory requirements, making new research discoveries, pioneering progressive policies, and finding new ways of training professionals and engaging the public.

In the first of the Water Environment Federation’s new Stormwater Champions series, we interviewed Mike Rolband, founder of Wetland Studies and Solutions (WSSI; Gainesville, Va.). Rolband has left a significant mark on the Washington DC region by serving in numerous advisory roles in local and state government and has helped write laws for Virginia on wetlands issues and waters of the state. Rolband created Virginia’s first stream and wetland mitigation banks and is helping lead the shift toward low impact development (LID) with demonstrations that remain progressive nearly a decade later and continue to provide data and experience.

WSSI’s extensive green roof with intensive planting areas. The intensive soil depth is 10 to 23 cm (4 to 9 in), which helps the plants survive in the harsh roof environment. The green roof was the most expensive LID practice installed at WSSI at $342/sq m ($31.80/sf). Image credit: WSSI

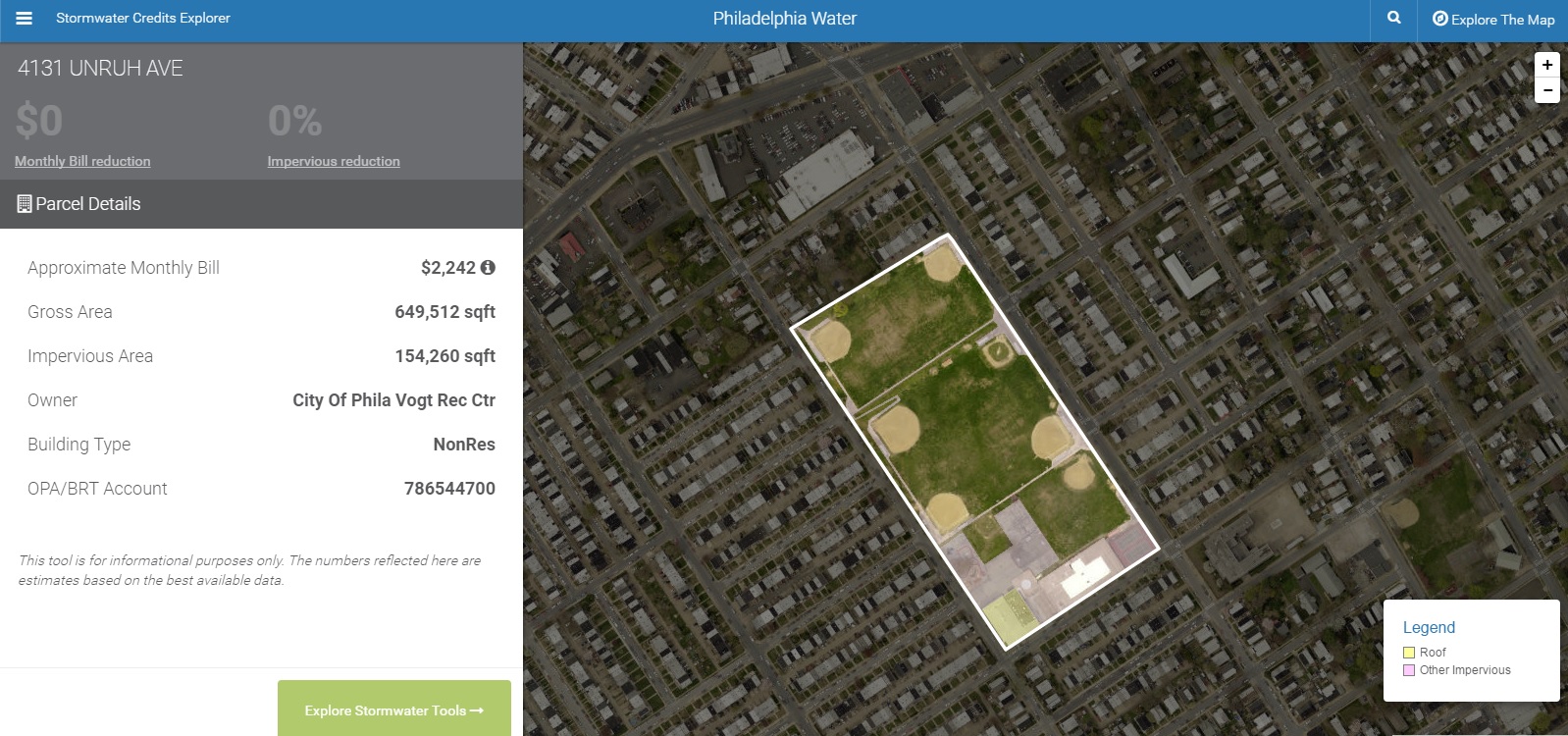

Pulling into the drive of WSSI, its surroundings immediately set it apart from other office spaces. Constructed in 2005 as Virginia’s first LEED Gold-certified building, company Founder Mike Rolband has swapped traditional concrete for various types of pervious pavement, and natural landscaping lines the building and parking lot. These pavers, however, are just one of seven stormwater LID practices at the site. Despite being built nearly 10 years ago, the building sports a number of features still considered progressive today, from a solar system that provides nearly 20% of the building’s power to rainwater cisterns for landscape irrigation and toilet flushing. In fact, the building’s LID facilities still put it ahead of Virginia stormwater regulations that went into effect this summer.

When Rolband enters the conference room for our interview, his two black Labrador retriever assistants accompany him. WSSI’s dog kennels and pet waste composter are among employee amenities, which also include, but are not limited to, a gym and wellness program, walking trail, and fruit and vegetable garden. Such amenities perhaps make the WSSI workplace the Google of the environmental consulting world.

A Regulatory Catalyst

WSSI refers to itself as a “natural and cultural resource consulting firm” and has worked on more than 2,100 sites in the Washington D.C. area, covering nearly 57,000 ha (140,000 ac). Rolband first was exposed to wetland issues working in the real estate development field. He started his own development company in the late 80’s focused on environmentally challenged sites. This company, now known as WSSI, evolved into an environmental consulting firm for developers affected by Virginia’s Chesapeake Preservation Act (Bay Act) and related regulations. Passed in 1988, the Bay Act is intended to balance economic development and water quality protection with a focus on reducing nonpoint source pollution.

Rolband was asked to determine how these early stormwater and water quality requirements interplayed with development, wetlands, and streams. In unraveling the new regulations, Rolband talked with numerous state and local agency staff, which was the start of his many and varied advisory roles over the past 30 years.

“The problem and the fun of regulation is that it is a combination of science and engineering, but it is also policy and economics,” Rolband said. He emphasizes the importance and difficulty of being able to translate complex technical information into regulations that the public finds acceptable and that solve problems economically.

The Bay Act is intended to preserve the integrity of streams and wetlands, and it paved the way for mitigation of these waterbodies. In 1994, through WSSI, Rolband helped create a wetlands mitigation bank, which was the first in Virginia and the fourth such bank in the U.S. When a public works agency builds a highway or a real estate developer impacts a stream, under the Clean Water Act, they have to compensate by restoring a stream or wetland elsewhere. “Historically that permittee would do the work, but wetland banking was an idea where an independent third-party entity, speculatively, proactively restores the stream or wetland,” Rolband explained. “They then sell the rights to that restoration to the company or entity that impacted the stream or wetland needing mitigation.”

In 2001, Rolband also helped create Virginia’s first stream credit mitigation bank followed by the state’s first urban stream bank in 2006.

Maintaining healthy wetlands and streams prevents further degradation of the Chesapeake Bay, which currently is impaired by nutrients and sediment. Wetlands detain stormwater, and they can remove nutrients and sediments from runoff. While streams do not provide detention, stream restoration typically reconnects the stream to the floodplain, increasing floodplain capacity. This slows runoff and streamflow, reducing the erosion of sediment and accompanying nutrients that occurs in unhealthy streams.

Wetland and stream projects also can create wins for wildlife habitat and public education. Rolband points to a stormwater wetland project done by WSSI in Loudoun County, Va., at the Broadlands. A boardwalk intersecting the wetlands has public education kiosks along its length. “On a nice day, you’ll see dozens of toddlers and their parents,” Rolband said. “At the same time you’ll see all sorts of birds and wildlife. The last time I was there, I saw a bald eagle perching, and all the people there were looking at the eagle.”

However, when it comes to creating multifunctional wetlands, the biggest challenge is a regulatory one, Rolband says. “Right now most regulators will not let wetland mitigation areas also serve as stormwater quantity controls.”

Walking the Talk

WSSI’s rain garden treats 3,220 sq m (34,660 sf) of impervious roof and parking lot area. It has a sizeable grass buffer, and drains to gravel bed detention. The rain garden cost $28/sq m ($2.60/sf). Image credit: WSSI

Responding to environmental regulations like the Bay Act, WSSI has grown to an 85-person team, which Rolband says represents anything but a traditional civil and environmental engineering firm. The staff includes only 15 engineers, and the rest are different types of scientists focused on wetlands, streams, forests, and historic resources. Its staffing has made the company well-positioned to work on LID. “It was a natural merger of the expertise and the regulations,” Rolband said.

For WSSI, LID as a stormwater solution came into play about 15 years ago when the company was hired to figure out what had gone wrong on some municipal bioretention projects and determine how to fix them. “LID became a very personal interest of mine. It seemed like a great concept, but there were a lot of examples of failures,” Rolband said.

Additionally, the Army Corps of Engineers began requiring LID as a wetland permit condition, so WSSI needed to understand it to help their clients achieve compliance.

An 84-m (275-ft) meandering bioswale with three check dams helps slow runoff before it enters an existing stream channel. The bioswale collects runoff from 1175 sq m (12,650 sf) and cost $40/sq m ($3.68/sf). Image credit: WSSI

When the WSSI office was built in 2005, Rolband decided to walk the talk and made the site an example of LID replete with pervious pavers, asphalt, and concrete as well as a green roof, two cisterns, and a bioswale.

The WSSI facility is in the watershed of a regional stormwater pond, so the stormwater controls constructed by the company were not required. From personal experience delineating streams and wetlands, Rolband has seen many waterbodies destroyed by stormwater after urban buildout. Conventional regulations for quantity control in Virginia definitely were not strong enough before July 1 of this year to prevent degradation of streams and wetlands, Rolband said. “I wanted to do what I thought was right, so when we designed this my goal was to mimic, as close as I could afford, the hydrology of a forested watershed.”

However, the LID practices were not constructed only to satisfy Rolband’s altruistic side, but also helped answer his client’s questions. This was “a demonstration project to show you can build LID practices, they can be successful, and they can look pretty,” he said. “The biggest question developers were asking was what does LID cost to build and maintain, and how long do these practices last.”

Demonstrating Success

WSSI’s concrete pavers reduce impervious area by 511 sq m (5,502 sf), and drain to an existing vegetated floodplain. They cost $76/sq m ($7.10/sf) to install. Image credit: WSSI

In December, the WSSI office will be nine years old, and its LID facilities have functioned without problem. Further, they have required little maintenance outside of adding new mulch to the rain garden and vacuuming the pavers.

For instance, a 15,000 L (4000 gallon) indoor cistern collects rooftop rainwater that is used for toilet flushing — a scheme approved by the Virginia Health Department contingent upon adding signage above toilets telling visitors and staff not to drink the water. The cistern, sized to meet toilet flushing needs 95% of the time, has provided a reliable source of water for at least 5 years. “We have never run out yet. We actually use less water than we expected,” Rolband said. Though a yellow sticky note about 51 mm (2 in) from the bottom of the tank marks a time when the tank running dry was narrowly averted by a last-minute rain event.

By actually constructing a full-scale LID project, WSSI has been able to demonstrate costs and maintenance needs and share lessons learned. “For example, we have a little bit of gravel pave, and we learned that it is a bad product to use in an area where you have turning movements,” Rolband said. After analyzing various bioretention soil media in failed projects, WSSI also has found that some soil types react with sodium chloride rock salt, and permeability can decrease by a factor of five or more.

The schedule for vacuuming permeable pavers is always a big question too, Rolband said. “My answer is that it depends on the users, land use, and vegetation.” At WSSI, their schedule is based on leaf fall because of the box elders, red maples, and pine trees lining the parking area, which drop needles and winged seeds. On other projects, maintenance professionals should look for dirt or trash accumulation.

When WSSI cannot provide a guided tour of its LID facilities, visitors can read the signage posted at each practice. WSSI also has a training room where staff and local government employees can learn from each other and invited speakers. Image credit: WSSI

The facility has served as a living laboratory of sorts, and until this year, WSSI was monitoring flow rates on all of its practices. It found that peak flow rates were far less than forested flow rates, though the volume leaving the site was still higher.

Practices installed at WSSI have provided Rolband’s team with experience and monitoring data, and have demonstrated to local decision-makers and developers the value in LID. “Instead of specifying something that is not going to work, then having LID given a bad name, we can show them it has a good name,” Rolband said.

New Opportunities

This spring, WSSI was brought into The Davey Tree Expert Company, which is a professional tree service group. According to Rolband, Davey Tree originally became involved in stormwater primarily from the angle of urban street trees and their stormwater benefits. So far it has been a very positive experience, Rolband said. “They are giving us, number one, a lot more depth in expertise on the natural resource side. We have about 15 arborists; they have thousands of arborists.” The acquisition also is providing WSSI the capital to grow, with plans to expand into the Maryland and Southern Virginia areas, and finally, it gives WSSI staff additional growth, learning, and travel opportunities as well.

In managing stormwater, “it is not just engineering anymore, it is also environmental science, it’s arborists, and urban foresters. We have to all work together, and that is what Davey Tree is trying to do.”

Well written article. Kudos to Mike and WSSI. Glad to see someone highlighting the good work they have done.

Doug Beisch

Principal

Stantec