Predicting major flood events before they occur can mitigate loss of life and better protect critical infrastructure, and so the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) considers flood-risk mitigation a crucial aspect of public safety.

According to the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), flooding ranks highly among the nation’s most costly natural disasters. Since 1980, instances of severe flooding in the U.S. have caused roughly $150 billion in damages and taken more than 600 lives, NOAA data describes.

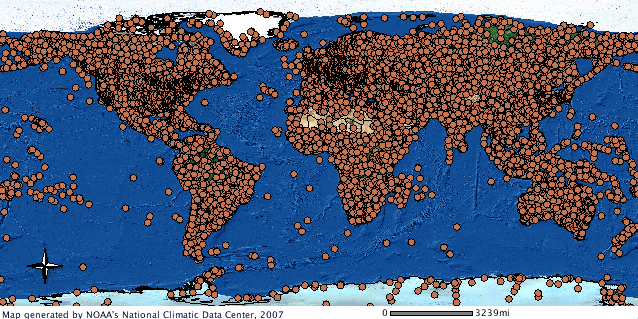

Since 2016, the DHS Science and Technology Directorate (S&T) has been working alongside scientists, equipment manufacturers, and stormwater utilities from around the U.S. to develop deployable, scalable, and low-cost flood-sensor networks. Designed for long-term deployment in flood-prone areas, DHS’ wireless sensors automatically detect rising water levels and send early flood warnings to officials and citizens. They require little or no maintenance, and cost less than $1,000 per unit – as much as 20 times cheaper than permanent flood sensors currently on the market, according to an agency fact sheet about the sensors.

DHS recently concluded a 3-year pilot test of the sensor networks in partnership with Charlotte-Mecklenburg Storm Water Services (SWS). In addition to identifying ways to improve the sensors, the test informed a new DHS guidebook that helps U.S. municipalities in urban areas manage their flood risks at minimal cost.

Testing Underway in Charlotte

Mecklenburg County, North Carolina, is one of the nation’s fastest-growing metropolitan areas. Over the last three decades, Charlotte–Mecklenburg SWS has taken a proactive approach to mitigating flood risks associated with urban development as their region experiences a population boom. While SWS already maintains a robust network of sensors for rainfall and streamflow throughout its service area, DHS saw an opportunity to improve the utility’s flood-prediction capabilities by implementing their new sensors.

David J. Alexander, senior science advisor for DHS, described that the Charlotte–Mecklenburg region provided an excellent testing environment for the sensor networks, featuring both prevalent flooding issues and strong local expertise.

“Charlotte stepped up to the plate offering a unique opportunity to evaluate and demonstrate new risk methods and technologies in a living laboratory that experiences inland and urban flash flooding and occasional hurricane-related flood events within a large and growing metro area,” said Alexander in a September DHS release.

The partners identified a diversity of flood-prone sites throughout the Charlotte–Mecklenburg service area where enhanced flood detection would provide actionable information for more populated areas. In total, they deployed 118 sensors along low-lying roadways, bridges, wastewater lift stations, dams, and more.

Since their implementation, 100% of the deployed sensors have met or exceeded standard metrics for accuracy, DHS described, entailing only a fraction of the typical capital and maintenance costs of comparable sensor networks.

“The partnership between Charlotte–Mecklenburg SWS and DHS S&T has been very productive — at both the local and national levels,” said SWS Director Dave Canaan in a release.

Reproducible Lessons

The North Carolina trial, which concluded its monitoring phase in February 2020 but will remain in place through spring 2021, taught DHS much about the semantics of deploying sensor networks that focus specifically on providing early warnings about flooding. Earlier this year, the partnership developed Low Cost Flood Sensors: Urban Installation Guidebook to pass on lessons learned to other growing U.S. municipalities.

The guidebook provides details on selecting the most effective sites for new flood sensors; how to acquire, install, operate, and maintain DHS sensors; and ways to optimize the sensors’ performance based on real-world feedback from Charlotte–Mecklenburg County stormwater professionals.

“Our collaboration with Charlotte–Mecklenburg allowed us to modify the sensors and provide additional functionality specifically needed by local communities,” described S&T Sensors and Platforms Technology Center Director Jeff Booth. “Their knowledge, experience, and recommendations on installation, monitoring, operations, and maintenance will help other communities.”

For example, the testing period uncovered several concerns for management and maintenance. Powered by sunlight, the sensors underwent significant disruptions if cloudy conditions persisted for three days or more. Physical damage to the units — whether from fallen trees, in-stream debris, or vandalism — also presented an obstacle, affecting about 20% of the units during the trial period. Recommendations from Charlotte–Mecklenburg SWS staff helped DHS further develop the sensors to minimize these issues.

Alongside the county’s existing flood information network, implementing the DHS sensors means stormwater professionals can now monitor approximately 96% of the area’s flood risk at any time, greatly enhancing the region’s resilience against natural disasters.

Access the guidebook or learn more about the sensors at the DHS website.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Justin Jacques is editor of Stormwater Report and a staff member of the Water Environment Federation (WEF). In addition to writing for WEF’s online publications, he also contributes to Water Environment & Technology magazine. Contact him at jjacques@wef.org.