According to the results of a new study, residents of Chicago and Portland, Ore., are willing to donate significant amounts of volunteer hours — in addition to reasonable increases in their monthly stormwater bills — to help support and maintain green infrastructure. Image courtesy of Stevi Hunt-Cottrell/Water Environment Federation

Because green infrastructure is decentralized by nature, infrastructure managers often depend on participation from community members to ensure these systems can successfully mitigate flooding and provide sought-after co-benefits. This could entail volunteering time and labor to help maintain neighborhood green infrastructure projects or contributing funding to support upkeep activities.

According to a new study from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign (UI; Urbana) and Reed College (Portland, Ore.) researchers, a growing number of city-dwellers value green infrastructure as a worthwhile approach to flood management and water quality improvement — and are willing to donate time and money to support it.

“The results of our paper seem encouraging to cities, indicating that they might well be able to put together a network of people that could help with decentralized management of green infrastructure,” said Amy Ando, UI professor of agricultural economics and lead author of the study, in a release.

Support beyond stormwater fees

The team’s study, which focused on attitudes toward green infrastructure in Chicago and Portland, set out to determine the financial value locals ascribe to green infrastructure benefits, such as water quality enhancement and aquatic habitat improvement.

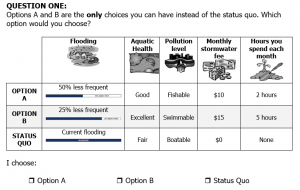

During the study, which involved several online surveys, respondents were asked to choose between two hypothetical infrastructure solutions and a status quo option. Each choice came with its own cost and volunteering demands as well as varying effects on flood prevention, aquatic habitat health, and water quality. Image courtesy of UI/Reed College

Researchers administered online surveys to nearly 700 residents of the two cities. Surveys first provided background information about the extent of issues related to stormwater management in their communities — i.e., flooding frequency and severity, the vulnerability of local wildlife, and how water quality affects health and recreation. Next, participants answered a series of questions, each asking them to choose between two potential green infrastructure-based solutions and a status-quo option. Each solution came with estimated ratepayer cost information and the amount of monthly maintenance work the solution would require, as well as a simple approximation of its environmental, social, and health-related benefits.

One question, for example, asked respondents to choose between:

- preserving current levels of flooding, “fair” aquatic habitat health, and “boatable” water quality at an extra cost of $0 and 0 volunteer hours per month;

- building infrastructure resulting in 50% less frequent flooding, “good” aquatic habitat health, and “fishable” water quality at an extra cost of $10 and 2 volunteer hours per month; and

- building infrastructure resulting in 25% less frequent flooding, “excellent” aquatic habitat health, and “swimmable” water quality at an extra cost of $15 and 5 volunteer hours per month.

Answers to the surveys revealed that support for green infrastructure is consistently high between residents of the two cities, but that the specific ways they value green infrastructure vary. Respondents in Chicago, for example, were generally more willing to pay increased stormwater management fees, but less willing to volunteer their time. Researchers observed the opposite among Portland respondents, finding a significant preference for volunteerism, according to the study. However, respondents in both cities reported that they would be willing to directly involve themselves in local stormwater management.

“We were surprised at the large stated willingness to volunteer that people indicated,” Ando said. “For example, the average respondent was willing to spend 50 hours a year on an ambitious project to restore aquatic habitat to excellent condition and water quality to be swimmable.”

Study findings detail a new way of understanding popular support for green infrastructure, Ando said, supplementing existing studies of how people regard green infrastructure in financial terms with their willingness to help maintain that infrastructure through hands-on labor.

“People are used to the idea that if there is a city fee, you have to pay it,” Ando said. “But volunteering is volunteering. You can’t force people to work.”

Don’t focus on flooding

Interestingly, participants responded affirmatively to infrastructure options that improve aquatic habitat health and enhance water quality more so than projects aimed primarily at reducing flooding. For example, results from both cities indicated that individuals would be willing to pay less than $0.50 more per month on average to reduce flooding by 10%, but more than $2 more per month to improve aquatic habitats to “excellent” quality.

Results indicated broad support for green infrastructure among respondents in both cities. However, infrastructure options that focused more on aquatic habitats and water quality attracted more support than options narrowly focused on reducing flooding risks. Image courtesy of UI/Reed College

“Often, when cities are talking about green infrastructure, they’re very focused on flood reduction. That was actually not the biggest value that we found. We found evidence that people place very high values on improving habitat for aquatic creatures in urban rivers and streams, and in reducing water pollution so the rivers and streams are more usable by people who live near them,” Ando said.

To attract local support for green infrastructure projects, the research underscores, utilities and infrastructure managers should promote new projects in terms of their benefits for local wildlife and recreational safety.

“One of the implications of our research is that urban water managers should be focused on providing those benefits and not just worry about flood reduction,” Ando said.

Read the team’s full study, “Willingness-to-volunteer and stability of preferences between cities: Estimating the benefits of stormwater management,” in the Journal of Environmental Economics and Management.