Despite slight improvements to the Chesapeake Bay’s dissolved oxygen concentration, underwater grass growth, and shoreside green spaces during the last 2 years, scientists monitoring the largest estuary in the U.S. graded the bay’s overall health as a D+ in their 2018 State of the Bay Report.

The assessment, published every other year by the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF; Annapolis, Md.), cites unusually wet weather in the Mid-Atlantic region in 2017 and 2018 as a major reason for the uncharacteristic decline in score. According to past reports, this is the first year since 2007 that bay health has declined.

“The good news is that scientists are pointing to evidence of the bay’s increased resiliency and ability to withstand, and recover from, these severe weather events,” said CBF Director of Science and Agricultural Policy Beth McGee in a statement. “And this resiliency is a direct result of the pollution reductions achieved to date.”

Bay health is the sum of many parts

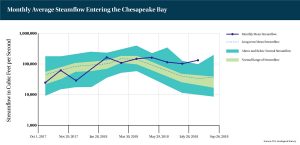

Summer 2018 brought unprecedented rainfall to the Chesapeake Bay watershed with record-breaking precipitation in Pennsylvania and Maryland. The extra streamflow carried large volumes of debris and pollutants into the bay and its tributaries, undermining long-term conservation efforts in the region. According to the newly released Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF; Annapolis, Md.) 2018 State of the Bay Report, rain was a major reason why 2018 was the first year in more than a decade that the bay’s overall water quality declined. U.S. Geological Survey.

CBF scientists work with conservation groups and governments to study 13 distinct indicators of bay health to come up with a comprehensive score out of 100 possible points. To do that, they work from monitoring stations and sensors distributed throughout the nearly 13,000-km2 (5000-mi2) Chesapeake Bay and its tributaries.

When English explorer John Smith first surveyed the Chesapeake Bay in the 17th century, his journals described in detail an unspoiled ecosystem lined with healthy forests and wetlands, containing crystal-clear waters teeming with sea life and underwater grasses. The partnership’s ultimate goal is to restore the bay to the state Smith encountered, which is what a perfect 100 out of 100 score would look like, according to CBF.

For 2018, the bay scored 33 out of 100, down from 34 in 2016.

Indicator-specific score changes since 2016 include

- 1- to 2-point increases in dissolved oxygen concentrations, underwater grasses, and “resource lands” such as forests and open spaces;

- significantly higher nitrogen and phosphorus concentrations and decreased water clarity, up to a 9-point drop; and

- no major changes in the amount of toxic chemicals entering the bay; buffer and wetland coverage; or oyster, crab, and rockfish populations.

Natural and unnatural obstacles

According to the report, causes behind the bay’s decline in health are a combination of extraordinary natural events and how bayside communities responded to those events.

Pennsylvania, one of the primary bay states most responsible for the estuary’s conservation, saw its wettest July and August on record in 2018. Virginia and Maryland also experienced a rainy summer, with July rains delivering the second-highest total precipitation in Maryland’s history. Extra rain means extra runoff, which brings larger amounts of nitrogen-and-phosphorus-rich agricultural and industrial byproducts into the bay.

Although Hurricane Florence missed most of the Chesapeake Bay area when it passed over the Carolinas in August 2018, the U.S. Geological Survey reports that flows coming into the bay were about four times greater that month than the monthly average.

On the Susquehanna River — the bay’s largest tributary — flows reached their highest in July 2018 since 2011. Flows exceeded 10,600 m3/s (375,000 ft3/s), or about 10 times the normal amount. The intense deluge forced Exelon (Chicago), who manages the Conowingo Dam on the river, to open the dam’s floodgates multiple times, releasing debris trapped behind its walls. In a statement, Exelon reported that the volume of debris they were forced to release downstream was the largest release by the dam in two decades.

Recent policy decisions at the federal level also are likely to undermine efforts to restore the bay and improve its resilience, said CBF President Will Baker.

“This is a challenging time for bay restoration,” Baker said. “Massive environmental rollbacks in clean-water and clean-air regulations proposed by the Trump Administration may make achieving a restored bay more difficult. Another restoration hurdle is the fact that science expects more extreme weather events in the future as the result of climate change.”

Progress varies by state

In 2010, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) used its powers under the Clean Water Act to set measurable, time-bound goals for each state and municipality touching the Chesapeake Bay to decrease its nitrogen and phosphorus contributions by 2025. By 2017, EPA’s Clean Water Blueprint required bay neighbors to have enacted at least 60% of the programs and practices necessary to meet their 2025 pollution reduction targets.

According to the 2018 update, states and municipalities bordering the Chesapeake Bay or its tributaries recorded improvements to the bay’s dissolved oxygen concentration, underwater grass growth, and shoreside green spaces. However, such water quality indicators as nitrogen and phosphorus contents increased significantly, resulting in an overall drop in water clarity. Eric Vance/U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Maryland, Virginia, and Pennsylvania face the blueprint’s most stringent reduction requirements.

Recent pollution reduction efforts in Maryland have been focused on wastewater discharges, according to a CBF progress report. While the state’s water resource recovery facilities (WRRFs) now meet 2017 goals for nitrogen and phosphorus reduction, contributions from urban and suburban runoff are on the rise, and excessive nitrogen output from agriculture remains an issue.

In Virginia, the problem is sediment. The state achieved its goals for wastewater discharges but failed to meet thresholds for sediment management from agriculture and urban runoff. Like Maryland, Virginia also struggles to curb nitrogen discharges from agriculture.

Results from Pennsylvania were less encouraging. Pennsylvania failed to meet its goals for nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment reduction from agriculture and runoff, though the state is within 5% of its 2017 phosphorus reduction targets, CBF said. Harry Campbell, CBF’s Pennsylvania executive director, says recent pollution-reduction efforts on farmlands, within watersheds, and in large cities are creating new momentum to bring the state into compliance with the blueprint. Inadequate funding, however, remains an issue.

“Now is the time for Pennsylvania’s elected leaders to accelerate this momentum by investing in the priority practices, places, and partnerships that will bring the plan into reality,” Campbell said.